in Listowel Town Square

<<<<<<<<

My Visitors on The Greenway

Photos: Carine Schweitzer

Bobby Cogan

These roadside rapid repair stands were a feature Bobby and Carine had not encountered before. A great idea.

Lovely to be out in the thick of unspoilt Nature

Carine and Bobby love the outdoors, walking, hiking or cycling. These lovely pitstops were a welcome respite.

<<<<<<

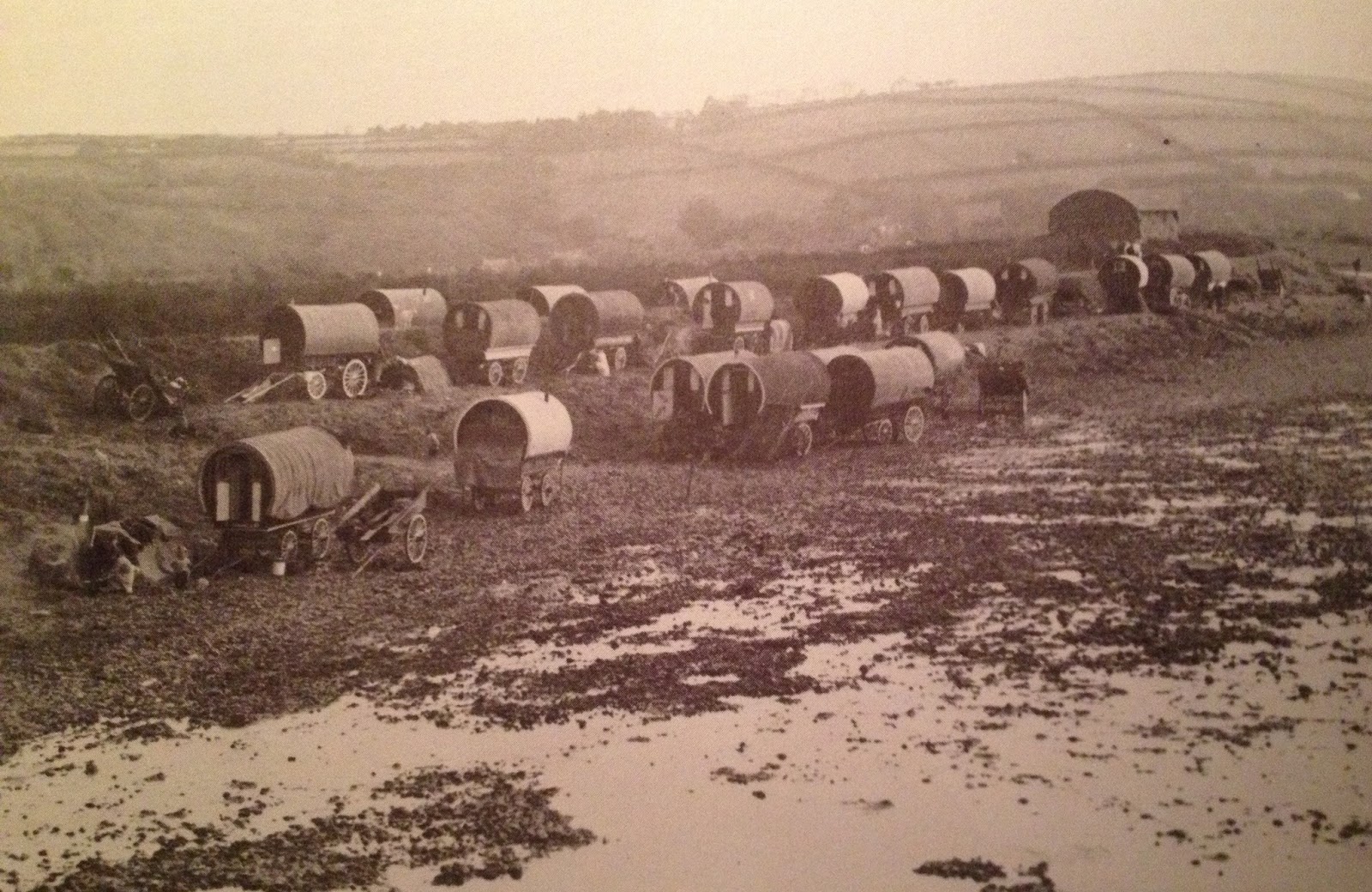

Irish Travellers in the Old Days

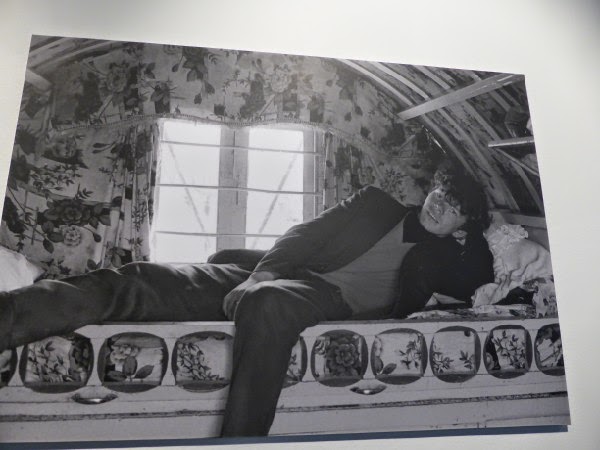

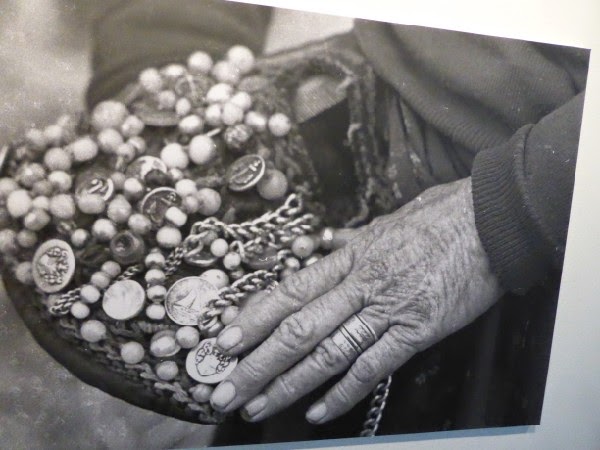

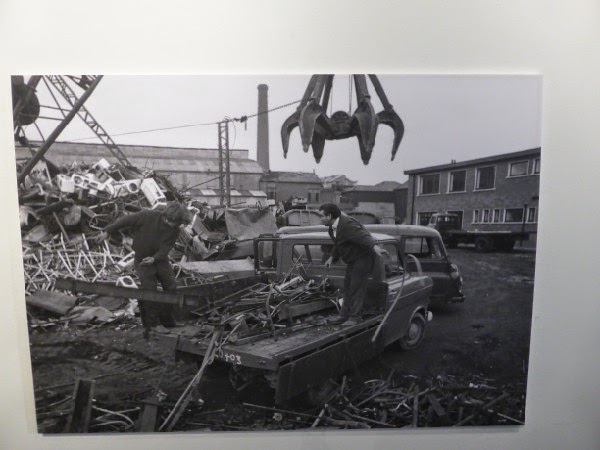

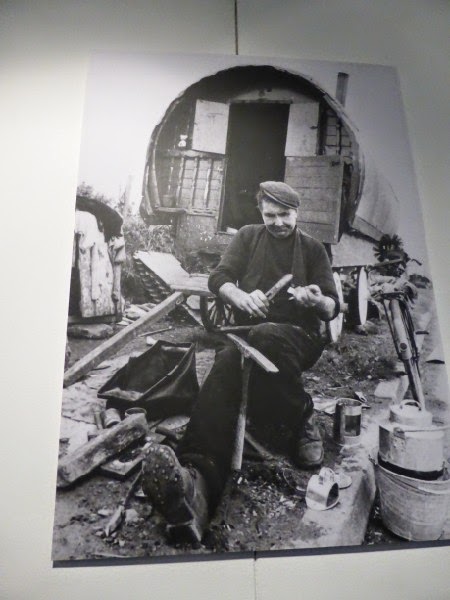

This photograph from The National Gallery’s collection was taken by a famous travel photographer, Inge Morath.

In the photograph is a Traveller family, in a convoy of barrel top caravans on their way to Puck Fair in Killorglin in 1954.

The following essay is taken from a website called Tinteán

The article was written in 2021.

By Frank O’Shea.

In Ireland today there are about 30 000 people referred to as Travellers. Just over two years ago, the Irish parliament recognised Travellers as a distinct ethnic group within the Irish population. This was a hugely significant decision for Irish people who always regarded ourselves as homogeneous. It was also of course significant for the Travellers, because it went a long way to restoring their self esteem and pride in their heritage. Interestingly, the decision does not create new rights and has no implications for public expenditure.

So who are these people we call Travellers? They used to live mostly in caravans or mobile homes in which they travelled all over the country or into England. They have Irish surnames – Ward, Connors, Carty, O’Brien, Cash, Coffey, Furey, MacDonagh, Mohan. In recent times, some have moved into the settled community; the town of Rathkeale in Co Limerick, population about 2000, has about 45% Travellers.

That the Travellers are a distinct ethnic sub-group within Ireland has been recognised as a result of recent research. To summarise that research:

- The Travellers are not part of the Indo-European Romani groups found in Europe and the Americas.

- Genetic studies have shown that

- The Travellers are genetically Irish

- There are subgroups within them

- There is a suggestion of strong origins from the midland counties

- It used to be thought that the Travellers owed their origins to the Irish Famine or to the Huguenots who came to Ireland from persecution in France and were able to buy out small farms, but the new studies suggest that they go back much farther, as much as 1000 years.

- The most reliable evidence shows that this distinctiveness from the local Irish population goes back between eight and 14 generations. Taking 11 generations as a reasonable median, this has given a possible origin as following the Cromwellian era.

- Another set of researches has shown that a particular allele (a variation of a gene) is found in 100% of Travellers, but in only 89% of the settled Irish population. This may be due to the long tradition of intermarriage within the community, but could also be interpreted as a sign of a possible ‘Abraham’ of all Travellers.

There is a unique Traveller language, variously known as Cant or Shelta or Gammon. This is quite distinct and has echoes in their spoken English. It contains words from Italian and Latin but its vocabulary is mainly Irish, sometimes in a clever anagram. For instance in Gammon the word for whiskey is scaihaab = scai + haab = anagramatically isca baha = phonetically uisce beatha, the Irish for whiskey. Likewise, the Shelta word for door is sarod, which is the Irish word doras backwards. For the Irish Travellers, Shelta or Gammon is usually regarded as a kind of code used deliberately to maintain privacy from settled people.

As well as their own language, travellers have a kind of semaphore for communication. For example, the rags which they leave attached to bushes when they move from a particular halting-place are significant. Red and white rags indicate that it was a good place; black or dark-coloured cloths tell of sickness or trouble with locals. In their folklore, as in that of many gypsies, the colour red has an important part to play as a protection against the Evil Eye.

In the middle of the last century Bryan MacMahon, the Listowel playwright and novelist, became friendly with the Travellers, learning their language and moving easily among them. He has written extensively about them, both as fact and in fiction.

One paper which MacMahon wrote for the American Museum of Natural History attracted great attention. He received dozens of requests for transcripts of the article and for further information. Most of these requests were from university research schools, but some were from organisations with military or secret service connections. Intrigued by this, MacMahon enquired why his work should create such interest. He was told that in modelling the behaviour of people in a post-holocaust situation, useful guides were provided by marginal tribes like the Lapps, the Inuit or the Irish Travellers. All have survived harsh social and climatic treatment and have learnt to adapt to the most inhospitable of conditions.

There can be great poverty among Travellers, especially those who move into the big urban areas. In campsites on the fringe of Dublin, conditions are primitive and unhygienic. Yet most caravans have a television and many have a satellite dish.

I now refer to my understanding of the Travellers from my growing up in Ireland. In the first place, we called them tinkers, a term that was not used pejoratively: this was a time when, if your kettle or cooking pot had a hole in it, you did not throw it out, you had it mended and if you were lucky, the tinkers were in the locality and they did it perfectly. They were tinsmiths and if we called them tinkers, we were not aware of any offence. It is possible also that the word is a version of tinklers, people who do lots of small jobs.

They would come to our part of Kerry for patterns and fairs or simply on a wide tour which covered our area at about the same time each year. Sometimes the children would come to school for a few weeks and we were always told to treat them with respect and kindness. There were occasional all-in fights between families but never with locals. Farmers might get angry about piebald horses grazing in their fields, while their wives became more alert in counting their chickens but in general there was a Christian tolerance for these people, ‘God’s gentry.’

Sometimes they would sell holy pictures or little statues and we would buy one or two. They were then and still are, strongly Catholic in their beliefs and practices. They had a strong moral code: teenage sex was a particular concern and it was common for girls to marry at 16-17 and men 18 or 19. They did not marry outside their own people, and marriages between first or second cousins were not unusual.

When they were in the area, their women might come to our back door and ask my mother for a jug of milk or a cup of sugar, which would be given without hesitation. Sigerson Clifford, the Cahirciveen poet writes fondly of them. Many of the poems in his Ballads of a Bogman are devoted to them and to stories about them, always told with respect and great affection.

The tree-tied house of planter

Is colder than east wind.

The halldoor of the gombeen

Has no welcome for our kind.

The homestead of the grabber

Is hungry as a stone;

But the little homes of Kerry

Will give us half their own.

From The Ballad of the Tinker's Wife.

<<<<<<<<

A Fact

James Naismith, a Canadian, invented basketball in Massachusetts in 1891. It was 21 years before it occurred to anyone to cut a hole in the bottom of the basket

<<<<<<<<<