River Brick from Ballinagare Bridge

Photo: Bridget O’Connor

<<<<<<<<

Home Truths

An extract from Dick Carmody’s memoir

Growing up around Clounmacon School, we were scarcely aware of the riches of history, culture, folklore and, indeed, nature that were in abundance all around us.

Our history and geography lessons often focussed on people, places and events far beyond our native shores. Little did we realise that our own country, county and locality contained a virtual repository of all the elements that make for a vibrant and viable community. As we left our homes and town lands we would soon come to realise what it is that moulded us and what would become that invisible thread that draws us back to our roots.

All around us we had people who were enterprising and resourceful. Families were relatively self-contained and self-sufficient in material terms while the spirit of comharing and co-operation provided that extra support and re-assurance to allow people to become part of a wider community. Whether working the land, playing our national games or in pursuit of religious duties, we were ever in each other’s shadow.

Despite the passage of time, there remains a strong sense of local identity, a sense and a pride of place that transcends the many changes that have taken place, including the advances in communications and technology.

The North Kerry landscape is like a tapestry of farms and bogland, separated by a network of roads, pathways, rivers and streams. Individual holdings, in turn, are comprised of fields, haggards, farm and domestic dwellings divided by ditches, dykes, walls and hedging. The quality of land has been greatly improved over the last half-century or so through the public drainage schemes and through land improvement initiatives by landowners themselves. Mechanisation of most farm work and the advances in farm machinery have greatly facilitated this. Demographic, economic and other changes have contributed to the decline in small farm holdings as a way of life and the resultant consolidation of farm activity among a smaller new generation who choose farming as a viable business and career.

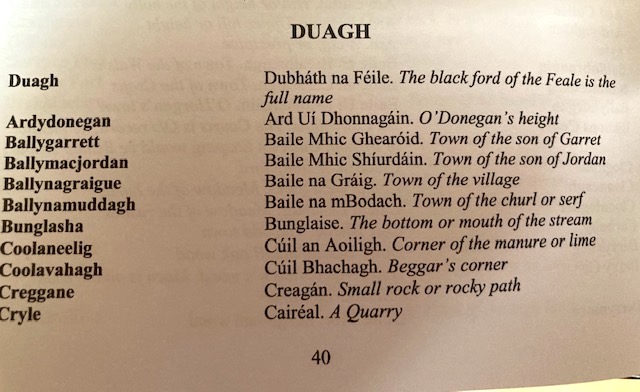

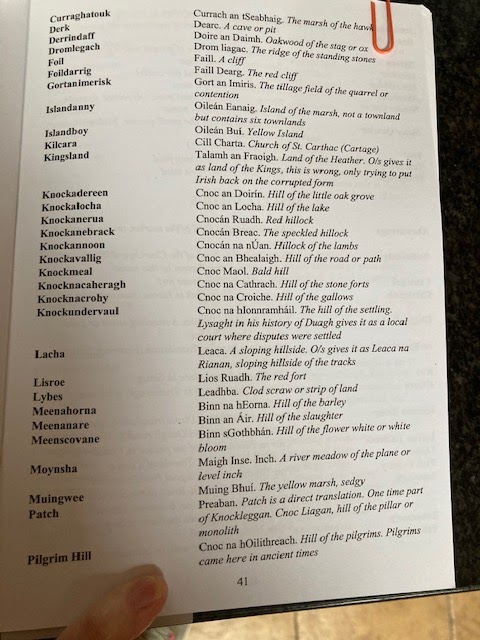

Despite all the changes that have taken place in the community and on the land, there remains for us a wonderful and rich legacy that is the range of placenames which adorn our local landscape. These names originate from the Irish language but through political or other influences have become anglicised and diluted over time and yet have not lost their distinctive and descriptive origins. Thankfully, through the work of local historians and scholars, together with the more recent interest in genealogical research both within Ireland and by an increasingly enthusiastic Irish diaspora, local placenames and town lands now have a new and even greater relevance.

Clounmacon Cluain Meacan The meadow of the root or tuber

Clounprohus Cluain Pruis Meadow of the fox’s lair

Clountubrid Cluain Tiobrad The meadow of the well

Coilagurteen Coill na Goirtin Wood of the little gardens

Coolatoosane Cuil an tSuasain The corner of the long grass

Coolaclarig Cuil an Chlaraigh The corner of the wooden bridge or structure

Derry Doire An oak wood

Dromin An Dromainn The little ridge

Ballahadigue Bealach an Daibigh The route of the tub or vat

Ballygologue Baile Gabhloige Townland of the fork

Bunaghara Bun an Ghearrtha The bottom of the cutting

Knockane Cnocan na Croise Hillock of the cross

Kylebwee An Choill Bhuí The yellow wood

Meen An Mhín Smooth green patch of land

Pollagh Pollach Place full of holes

Skeherenerin Sceiche an Iarainn The Bush of the iron

Placename translations and interpretations courtesy of ‘Logainmneacha – Placenames of North Kerry including Tralee and Ballymacelligott’ by Dan Keane, 2004.

<<<<<<

January 2 2013

On the evening of January 2 2013, we had a spot of unwelcome excitement at Craftshop na Méar in Church Street. We had a chimney fire.

Because it was a three storey building, putting out the fire was a big operation. I took some photos of some of our saviours on the night.

Meanwhile down the road people were queueing for the pantomime unaware of the drama going on a short distance away.

<<<<<<<<<<

Tracing his Listowel Connection

Every so often I get an email from someone who is anxious to trace his Listowel roots. I’m printing Paul O’Connor’s email in the hope that someone will know something about his Charles’ Street family.

Hi There

I came across your page while looking for information on Listowel. I’m doing up some family history and tracing the roots. My great grandfather Daniel Connor was born on 27th November 1881 and the address was given as Charles St Listowel. In 1896 his grandfather also Daniel Connor died and the address is given as Charles St.

I was wondering was it a house or was there a kind of workhouse there.

Any information would be greatly appreciated

Thanks

Paul