I met these 3 lovely ladies in the St. Vincent de Paul shop on Thursday last. Tina, Helen and Eileen do great work. Take a bow, ladies.

The very next day I was in the shop again and I took this photo of Pat Dea who is their invaluable helper in the watch and clock department. He was returning a clock that he had restored to working order.

Pictured with Pat are volunteers, Eileen O’Sullivan, Mary Sobieralski and Hannah Mulvihill.

<<<<<

Here we go again

Roadworks on the Tralee to Listowel Road on May 9 2013. It’s all good news though, as this time I was diverted onto a stretch of the new road. The journey to Tralee from Listowel is getting shorter and more enjoyable.

<<<<<<

Bridge Street, Newcastlewest 1900

<<<<<

Sunday last, May 12 2013 was Mothers’ Day in the U.S. Sean Carlson, whose mother hails from Moyvane, wrote this lovely article in USA Today;

My grandmother gave birth to 16 children over the course

of 24 years.

Growing up, my grandmother talked

about becoming a teacher.

Instead, she gave instruction in a

different way: a living example of love and perseverance.

When I was

twelve, my mom and I often shared a cup of tea when I arrived home from school,

just as if she were still living in Ireland. Listening to her recount memories

of her childhood there, I told her that someday I would write her story.

“What story?” she said. “If there is a story to share, it

belongs to my mother, your grandmother, Nell.”

Her

mother, my grandmother, Nell Sheehan, lived her entire life in the rural

southwest of Ireland. In a different time and a different place over the course

of 24 years, from age 23 until 47 she gave birth to 16 children — eight

daughters, eight sons, no twins. My mom was the 15th.

Motherhood

may have been her calling but growing up, my grandmother had done well in

school and talked about becoming a teacher. That option ended with her

marriage, as such jobs were scarce and available either to single women or male

heads of households, but not allowed to be hoarded by two workers in the one

family. Instead, she gave instruction in a different way: a living example of

love and perseverance.

Although

unable to pursue the possibility of a career outside the farmhouse where she

settled, she insisted that her daughters receive an education or other chances

for advancement. The local primary school, a simple building with two

classrooms, stood within walking distance at the top of the lane. The boys

often stopped attending on account of the farm work. Most of the girls,

however, continued their education. Their mother wanted her daughters to have

opportunities in their lives.

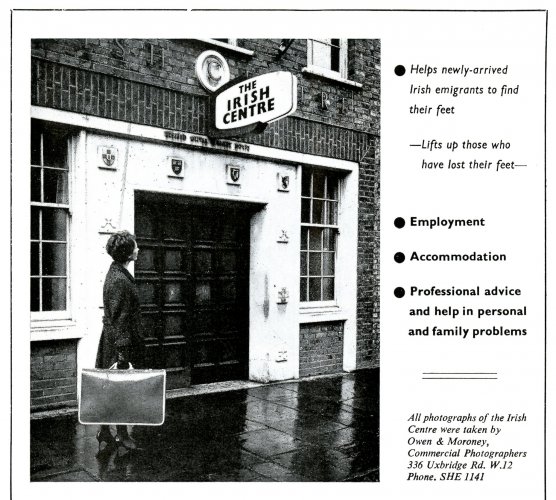

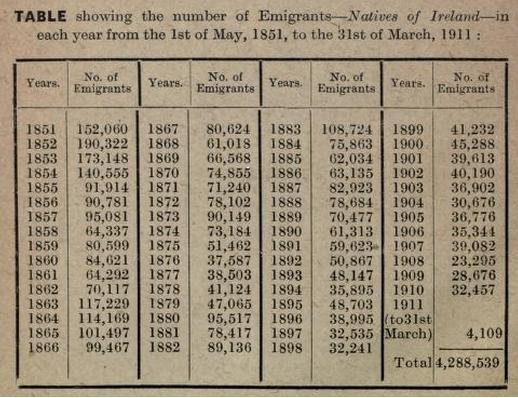

By

encouraging them to spend time away, the irony was that she destined her girls

for elsewhere. With bleak economic prospects at the time, little choice

remained for them to stay. One after another, they left home — almost all of

them for the United Kingdom or the United States. Every night, their mother

prayed for their protection.

Despite

the distance, the mother-child relationship stayed strong through the letters

they wrote: accounts of life in new lands, photographs of grandchildren born

abroad. In this way, my mom learned about many of her sisters and brothers. Her

mother held the notepaper close to her chest, near to her heart, savoring the

words as if the sender were present with her there on the page as well. Then,

she read them aloud to her husband and those still at home.

Almost

every envelope included a portion of their earnings as well. How difficult it

is today to imagine enclosing 20% of a weekly salary. Yet, this is what the

children often did for their mother, pleased to think of her being able to buy

fresh tomatoes as a treat or perhaps a haircut in town. After the arrival of

electricity in the area, her oldest son and daughter-in-law bought her even

greater gifts that transformed her life in the home: a washing machine and

later a stove.

My mom

followed in the footsteps of her siblings. Shortly before turning 17, she went

to London with her sister. Whenever she returned home afterwards, traveling by

train, car and ferry, her mom greeted her at the front door of the thatched

farmhouse, so eager for her arrival. Walking her daughter into her room, she sat

on the bed and tapped her hand against the mattress, saying, “tell me all

that has happened since you left.” My mom would then recount the latest

from her sisters and brothers, as well as her experiences away from home.

As her

daughters grew up, my grandmother sometimes confided that she looked forward to

the day when they would return to live nearby, hopefully raising families of

their own near her, able to visit as she aged. Although they didn’t come back

for good, still they remained close. They may have left, but their mother was

with them wherever they went.

A few

years ago, I found a cassette recording from a distant cousin in Florida who

has since passed away. On one of his visits to Ireland decades earlier, he

recorded a conversation with both of my grandparents. As my mom listened to her

mother’s voice for the first time in more than 30 years, the tears came.

Memories flooded back, reminders of the imprint of a mother.

Like every

year, they are there on Mother’s Day. They are there every day.

Sean Carlson

is completing a book about emigration through the lens of his mother’s

experiences, from Ireland to London and the United States.

(This story will be familiar to so many others. I have heard other versions of it recounted in my knitting group by some of those lucky enough to make their way back home, sadly not before the mothers they left behind had passed on.)

<<<<<

Some people I snapped on Vintage Monday

4 Generations of Barretts

Anthony and Nuala McAulliffe and Jim Halpin

4 Bombshell Belles

Dan Neville ready for road

<<<<<<

Ballybunion at night courtesy of Ballybunnion Sea Angling

<<<<<

John Kelliher took the Knockanure communicants on their big day.